We all know that car and motorcycle design studios are packed with supercomputers. But they still rely heavily on low-tech, life-size models too, produced by skilled clay sculptors. And that’s even true of cutting edge companies like Tesla.

Richard Mitchell is a clay sculptor for Tesla: he’s responsible for fine-tuning the complex shapes of world’s best-selling plug-in electric cars. “I love creating something unique that you can see and touch, all from a two-dimensional drawing.”

He’s helped design some of the most futuristic cars on the road, but he’s also got a thing for classic and custom bikes. In his early 20s he started getting into vintage motorcycles—and specifically English marques like BSA, Triumph, Norton and Vincent.

“For years I’ve kicked around the idea of building one,” he tells us. “The only bike I’ve built before was a mildly custom 1971 Honda SL-125. And although I’m mechanically inclined, there were skills I lacked.”

Those feelings of doubt slowly faded after Richard moved to Los Angeles in 2010 and began working for Tesla.

It was an exciting time: the company was still small in those days, so Richard found himself rapidly skilling up to handle occasional welding, fabrication and painting duties for the prototypes.

“But outside of work, I was bored—and wanted a personal project for my free time,” he says. So he placed a Craigslist ad, looking for a BSA motorcycle “and/or parts.”

Within hours Richard got a message from a guy with a BSA Thunderbolt. “I went to check it out. It was a true basket case: the bike was in about a dozen boxes. But it did seem to be ‘all there’ and it included a non-numbers matching but complete engine and an unmolested frame.”

The original plan was to do a quick build: a simple, stripped-down bobber with black paint and off-the-shelf parts. “I figured it’d take about 6 to 12 months to complete,” says Richard. “But none of this came to be true!”

The closer the BSA got to being a roller, the more ideas sprung to mind. Extra components were tracked down, measurements and drawings were made, and parts machined.

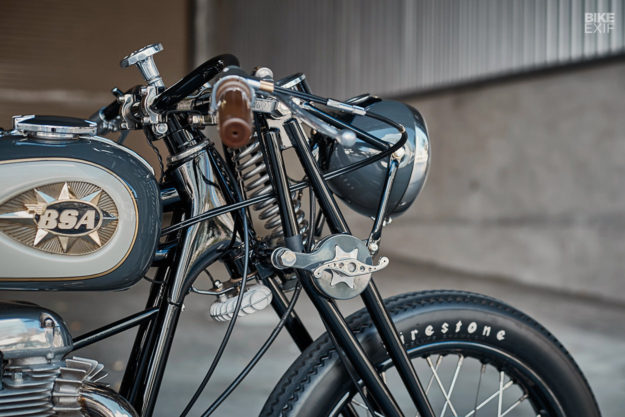

“Somewhere along the line, a theme emerged,” says Richard. “I wanted to take the late-model unit-based BSA and make it appear as if it had been dreamt up in the 1940s or 1950s.”

“I wanted to hide anything modern, and anything off-the-shelf I would try to modify or merge with hand-made pieces.”

The engine was taken care of too. It turned out to be a perky 1966 A65L (Lightning) engine, and Richard got it meticulously rebuilt by his good friend John French. The crankshaft was rebuilt too, and new rods added.

SRM provided a new camshaft and high volume oil pump. The cases were machined for new bearings and bushings, and the barrels were machined .040” over before new pistons and rings were installed.

The dual carb cylinder head was cleaned up, and new valves, guilds, and springs were installed. On went a set of polished Amal 930 carbs—the Premier spec version with a hard-anodised slide and precision-engineered idle circuit.

Gases now exit via a modified set of BSA Wasp scrambler exhaust pipes.

Turning his attention to the 1968-spec frame, Richard started by removing the factory swingarm and seat mounts so that he could weld a custom hardtail into place. The rear section, built by David Bird, drops the bike 2.5” and lengthens the wheelbase by 4”.

Jake Robbins of Vintage Engineering in England built the custom girder fork, amplifying the vintage look Richard was after. Then Richard redesigned the friction levers and water-jetted new ones out of steel to make them more unique.

He also built a new lower yoke, slightly changing the geometry to give the front end a bit more rake, without going outside the limits of the factory steering damper.

One of Richard’s favorite pieces on the bike is an eBay find: a 1952 Smiths Chronometric ‘Revometer’ speedo. He’s also fond of the original Lucas aluminum heat sink and the zener diode, a regulator that sends excess voltage back into the frame when it reaches a threshold.

Each wheel is completed with powder coated hoops, new stainless spokes and period-correct Firestone tires—3.25-19” at the front and 4.00-18” at the back.

The front brake is a BSA twin-leading shoe, with extra detailing and brass mesh vents added, and the rear brake is a BSA quick-detach ‘crinkle hub.’

Richard’s made a few special pieces for the BSA, including the battery box—which holds a 4-cell lithium battery, the voltage regulator, and a 20-amp fuse.

He also built an oil catch-can that does double-duty as a breather, and a brass tube to hold the bike’s registration papers, mounted to the license plate bracket.

To avoid using zip-ties, he’s made about a dozen leather straps with aged-brass snaps to hold the vintage-style cloth-covered electrical wires to the frame. The slender rear fender stays are custom-made too, with water-jetted mounting pieces—including the one used for the solid brass LED powered taillight.

“When it came to the paint, I wanted to do the work myself,” says Richard. “I chose two classic Porsche colors: Graphite Gray and Glacier Gray Metallic, which were both used on the 50th anniversary edition 911.” The result is worthy of a pro shop.

The low-key, sophisticated paint is offset with gold leaf striping—which, incredibly, Richard had never attempted before. “It took a few tries but I couldn’t be happier with the results. I added a little nod to the original BSA ‘Made in England’ decal, only now in gold leaf and relocated to the hardtail.”

It’s a breathtaking build. It’s also one of those rare machines that looks even better the closer you get to it. So last year, Richard took it to The Quail Motorcycle Gathering in Carmel, California, where it won second place in the Custom/Modified Class.

“This was a dream come true,” he reveals. “Getting that type of response for my first ground-up build meant a lot to me. It also got me hooked on wanting to build more.”

We hope Richard does continue building. Isn’t it reassuring to see someone immersed in the high tech world of Tesla applying their skills to an old-school build like this?

Richard Mitchell Instagram | Images by (and thanks to) Paulo Rosas of Speed Machines Design

RSS Feed

RSS Feed

7/23/2018

0 Comments